- Home

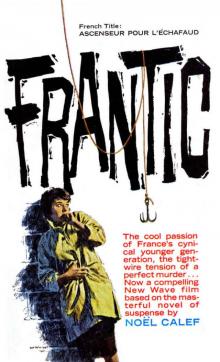

- Noël Calef

Frantic Page 15

Frantic Read online

Page 15

They didn’t press the point. They were satisfied.

In the courtyard, the red Frégate had been carefully parked. The questions began again:

“Does this vehicle belong to you?”

Again, he smelled a trap and carefully checked over the plate, the left headlight with the cracked glass, the cigarette burns on the dashboard and the torn stitching on the back seat.

“Yes,” he finally admitted, “it’s mine.”

They went back into the office. Julien felt he’d just lost a battle. He didn’t know which one. But he wasn’t beaten. He knew damn well he hadn’t killed those two poor campers. That he’d never even been in Marly. That he didn’t even know which road you took to get there …

“Julien Courtois, I charge you with assault by night, attack with a loaded weapon, theft and premeditated murder against and on the person of Pedro Carassi, Brazilian subject, and his wife Germaine, maiden name Tarivel, on the night of the twenty-seventh and twenty-eighth of April, 1956, at Marly-le-Roi, Department of Seine-et-Oise …”

He listened through to the end, then said, decisively:

“I must definitely protest. I didn’t kill those poor people. I couldn’t have.”

He stopped just at the edge of the abyss, his perfect but perilous alibi—the elevator.

That night, his first in a real prison, he drew up his balance sheet. He knew the enemy he had to fight, and the enemy seemed contemptible. The investigating judge—they always gave the job to lawyers too young or too timid to make it on their own. In the American films, they called him “the D.A.” Julien didn’t know why. There’d be a long, preliminary private-hearing to determine whether there was enough presumption of guilt to bring him to trial. That was all right with him. The lawyer assigned to his defense seemed a bright youngster. Let him talk; Julien would keep his mouth shut. He’d demand to see Geneviève. That one, with her jealousy, what a nice pit she’d dug him into! It wasn’t her fault, obviously, but it wasn’t his either! Careful with Geneviève! Careful with the lawyer! Say nothing, never, about Bordgris, the elevator. The Marly business would die by itself….

But he couldn’t sleep. Turning and turning again on his bunk, he felt like laughing.

“Listen, I’m the Bordgris case, you clowns! I’m the guy in the elevator!”

Then he hushed himself inside. Not a word. Then it would go like clockwork.

Chapter XIX

Questions, cross-examinations, testimony, confrontations.

For days, Julien stuck it out, sure of his innocence, confident and terrified, but fighting all the way, giving ground only inch by inch.

“Where were you on the night of Saturday to Sunday?”

“I decline to answer.”

“And on the night of Sunday to Monday?”

“I decline to answer.”

The investigating judge turns to the defense lawyer:

“Counselor, you’d better advise your client to pick some other grounds for defense.”

The lawyer—he’s all right, that boy—turns to Julien.

“For your own sake, Courtois, you must speak up.”

“Wants us to think he’s protecting a woman’s honor,” says the judge disgustedly. “Courtois, in the shape you’re in, if there is a woman, you’d better talk. It’s too late in the day for honor. It’s your head against her reputation.”

The lawyer tries a flank attack.

“Judge, give the woman he’s protecting time enough to come in and identify herself. After all, Courtois’ acting as a gentleman and …”

“There isn’t any woman, she doesn’t exist, Counselor; you know that as well as I do. He isn’t protecting …”

“I’m not protecting anyone,” Julien finished for him. “And I put my trust in justice. You can’t prove I committed this crime. For the simple reason that I didn’t.”

They take him away. They bring him back. Prison. Hearing room. Prison. The most astonishing thing is, witnesses recognize him. The old couple … where the devil did they crawl out from?

“Courtois,” the judge says, “here are two witnesses who saw you at Marly on Saturday night, all day Sunday and the night of Sunday to Monday.”

Julien, who has the light in his face, moves to get a better look at the husband and wife. They wrinkle their brows, look at each other out of the corners of their eyes. The man hesitates …

“About the right height … but he kept hiding his face …”

“Excuse me,” his wife intervenes, “you run a hotel, you get to be a psychologist. I say it’s him.”

The defense lawyer is quick to seize the smallest detail and mount it on a pin.

“One moment. There is a contradiction here. One, you said your electricity was out, two, that the man hid his face. In that case, could you explain to me just how you can be so positive, although your husband …”

Mathilde gave him a superior smile.

“Monsieur, the difference between a man and a woman is intuition.”

“Madame, justice is only interested in the facts!”

“You haven’t got enough facts?” the judge asks. “The car? The name the mysterious tourist gave: Courtois? The murder weapon? And don’t forget the raincoat.”

Why did they all have a thing for his raincoat?

“Nevertheless,” the lawyer says, “the two testimonies cancel out. The wife says yes; the husband says no.”

Charles turns, red with anger.

“Pardon me! I didn’t say no. I just didn’t say yes.”

“Logic,” Mathilde adds.

They are definitely getting on Julien’s nerves. The wife nudges the husband, saying:

“I’ll tell you what throws you off, Charles. He’s dressed differently. First he had a turtle-neck sweater, and then we only saw him in his raincoat, remember?”

“A turtle-neck sweater!” the lawyer shouts. “You see? I’ll bet my client doesn’t even own one.”

Julien shrugs. He should’ve demanded a more experienced lawyer, more cunning.

“But I do own one. I wear it for the country,” he says.

“And the country was where you were going,” the judge says, “you told the janitor of your building.”

“But I don’t deny it! Only, if I’d gone straight from my office, I couldn’t have put on the sweater; it was at home. And I was wearing a grey shirt. Same one I had on when I was arrested.”

“We’ll go into your comings and goings shortly, Courtois,” the judge says. “Let’s get back to what you told the janitor, if you don’t mind. You told him, just a minute …” He looks at his notes. Here it is … ‘I’m spending the week end with the most charming woman in the world.’”

Julien frowns.

“Yes, I seem to …”

The judge turns to the lawyer.

“Your client’s tying his own noose, Counselor; it’s getting too easy.”

“Not at all! Courtois’ told us that by the most charming woman in the world, he meant his wife!”

“Mmm. Then I wonder why he didn’t take her along with him?”

Julien nearly burst out laughing.

These guys are drowning in a glass of water. He didn’t take her along because he’d been trapped in the … He catches himself, hard. Shut up. Nothing about the elevator. The turtle-neck sweater and the charming woman are still being tossed back and forth. Just now, the judge seems to be getting the better of it.

“I’ll tell you a secret, Counselor. Madame Courtois can’t testify about the sweater being in the apartment over the week end. She wasn’t there. On the other hand, and your client confirms this, there’s a linen cupboard in the washroom next to his office.”

The defense lawyer has run out of arguments. He gives up, waving his hands to indicate it—a sweater, who cares. He turns to the innkeeper.

“Now, let’s agree. On the identification of Courtois, you’re neutral. Correct?”

Charles

doesn’t have time to answer. Mathilde addresses herself to the judge, going over the lawyer’s head:

“I’m sure my husband could be more positive if we could see Monsieur with his raincoat on.”

“Good idea! Put it on, Courtois.”

He obeys with ill grace. Say, he hadn’t noticed the tear on the left shoulder, must’ve caught it on something.

“Look at him now. Is that him?”

Charles makes faces, narrows his eyes, leans his head to one side and then the other. Julien, impatient, goads him:

“Well? I’m me, eh?”

Annoyed Mathilde answers at once:

“It’s him all right, no doubt about it.”

Charles says nothing, bites his lip. His wife urges him on:

“Come on, make up your mind, you can see it’s him … remember …”

The innkeeper raises his arms.

“Ah, what can you say, the way he kept creeping around in dark corners, turning his head …” He reminds Mathilde: “You know how it was! Kept hiding, didn’t want anybody to see him! You said yourself he must be cheating around … and that’s why he …”

“You see how confused you get,” Mathilde says firmly. “That’s not why he hid his face.”

“Ah, please!” the lawyer cries. “Don’t jump to conclusions!”

“Madame is right,” the judge says, “Courtois was planning the crime and didn’t want to be recognized later.”

They start arguing again. Mathilde joins in sturdily. With a little smile that means: intelligent people can always get along, Judge. As for Julien, there was something in the last thing the judge said … That was it!

“May I? If I understand correctly, the inquest established that the campers arrived Sunday morning. So how could I be planning the crime Saturday night?”

He is quite pleased with himself, and can’t see why his lawyer looks so hang-dog, or why the judge is grinning fit to split his lip. The judge clears it up for him.

“Ah, so you admit being in Marly?”

“Certainly not! That’s not what I meant.”

“Just an assumption, Judge,” the lawyer shouts. “Not an admission!”

“Your client’s trapped himself, Counselor.”

“No! No! No!”

Julien had shouted at the top of his lung-power. He pulls himself together. His lawyer is always the underdog. He’ll have to be all the more sharp, his safety depends on him alone.

“Judge, you still haven’t answered my question,” he says.

“Let’s say planning ‘a’ crime, that’s good enough.”

Now Julien divides his forces. Part of him is busy keeping down the truth that would sweep away the whole structure of accusation. The other part amuses itself watching men argue themselves hoarse over an error. The whole thing is ludicrous.; They’ll soon see their mistake.

Automatically, he is playing with the button on his raincoat when he gives a cry of surprise:

“Hey, there’s a button missing!”

His lawyer twitches in his seat.

“Don’t be alarmed,” the judge says soothingly, “we’ve found it.”

“Oh, in the car?”

“No. In the hand of one of the victims.”

Julien, turns pale. The judge turns to Charles.

“Now, let’s quit quibbling. You’re not sure you recognize the accused. But you formally identify the article of clothing he was wearing, is that right?”

“As far as that goes, yes. The last time, I even noticed the tear on the shoulder.”

“When did you notice it?”

“The last time. Sunday night.”

“He means early Sunday morning,” Mathilde adds.

“Thank you, Madame. And you both agree on another point; the tear in question wasn’t there before?”

“No,” says Charles. “I even thought, when I saw it the first time, there’s a raincoat I could use.”

“His is in terrible shape,” Mathilde interprets.

“That will be all. Thank you very much.”

Mathilde seems furious that there isn’t any more. She leaves with her husband. The door slams. Julien jumps up, then sits down again. The judge is laughing at the lawyer:

“Well, Counselor, we’ve just established strong presumption of premeditation.”

The defense counsel refers to the weakness of human testimony, and the judge falls back on the raincoat.

They take Julien away, while he makes a mental note: that raincoat might be his shroud. They bring him back. He’s decided to throw some ballast over the side. “I lied on one point. I didn’t wear the raincoat during the week end.”

By now, the overcoat would’ve been cleaned.

The judge smiles, and has Denise brought in. Incorrigible, she crosses her legs.

“I thought he’d be leaving with his overcoat on. But no, Monday morning I find this note …”

She establishes that, Monday morning, the overcoat was in the office and not on Julien’s shoulders. So, he left with his raincoat. The judge thanks Denise.

Julien follows her with his eyes, decides that her calves are too skinny and her behind too low, then comes back to his tormentor:

“Your deduction would be correct, Judge, if I hadn’t come back to the office Monday morning before Denise.”

“Imagine that.”

He doesn’t let him go on. They take him away. In his cell, Julien feels he is throwing more and more ballast over the side. The raincoat, coming back to the office.… Dangerous, giving it away like that, piece by piece.

They bring him back. This time, he finds himself face to face with Albert.

“Albert Chirieux, you saw Courtois leave the building Saturday night, at 6:30. Was he wearing his raincoat or his overcoat?”

The janitor puts his chin in his hand, shuts his eyes and purses his lips.

“I’ll tell you, Judge, I just don’t know.”

“Try …”

“I am trying. Only, Monsieur always wears gray, you know what.! mean? So it’s hard to tell.… And it wasn’t very light out …”

“All cats are gray in the dark,” the lawyer jokes.

Julien thanks him with a wink, but the judge isn’t satisfied.

“Think hard, now, Chirieux …”

“Well, if you want to know what I think, Judge, I think he was wearing the raincoat!”

The judge’s palm slams on the desk. Julien jumps. The lawyer waves his hands.

“Just the witness’ impression, influenced by reading the newspapers! An indictment has to be based on hard facts!”

The judge gets on his high horse.

“Hard facts? Still haven’t got enough? What about the murder weapon? What about the car? What about the button off the raincoat?”

The defense counsel wants to say something, the judge stops him and the lawyer seems relieved.

“And why,” the judge continues, “why didn’t Courtois tell us right away that he was wearing his overcoat? Somebody had to identify him in the raincoat, the raincoat had to become one of those hard facts you talk about, before he remembered he wasn’t wearing it. Why?”

He suddenly turns quiet and fires his last shot sitting down.

“All right, Counselor. He left in his overcoat, that’s all right with me. And then? By his own admission, the raincoat was in the car. He could have put it on any time.”

Crippling. The defense lawyer’s shoulders sag, while the judge’s chest swells.

“Now, let’s clean this thing up,” he says. “Chirieux. Was Courtois in the building Monday morning?”

“Like I told you, Judge, I thought he was.”

Another change. Hope on one side, disappointment on the other.

“But I made sure I was wrong,” the janitor says, and the expression on the two young men’s faces switch sides.

“That’s right, we’ve got your deposition. Thank you. Now, Courtois, what’

ve you got to say to that?”

“He wasn’t wrong,” Julien says firmly. “I was in my office. He tried to get in, but I kept the lock on.”

‘“Why?”

“Why? Why because I …”

Shut up. The trap! The terrible trap he keeps falling into. He still hopes this crazy Marly thing will clear up by itself. Say nothing about Bordgris. But Marly is a trap, too, snapping at his feet at every step. He pants, searches for a way out. Doors slamming everywhere. As soon as one seems to open, someone or something slams it in his face.

They slam louder and louder, echoing into the very depths of his body, his brain. But he holds himself together. His nerves are jangling. He’s gotten thin, his face has hollowed out. He’s gotten old, his stomach can’t hold food well now. He’s been sick twice in the hearing room. They accuse him of faking. His lawyer doesn’t even protest.

They bring him in; they take him out. But he holds himself together. Only, alone. For he is alone. Geneviève has deserted him. Georges couldn’t care less. His lawyer has given up hope.

They show him photographs. A man and a woman.

“Recognize them?”

He sobs:

“No! No! No!”

They bring him in; they take him away.

His lawyer demands psychiatric tests. He lets himself be examined, docilely, at the end of his tether. They find him responsible.

Ten days. On May 8, the doors stop slamming.

There is nothing definite. But the judge seems less sure of himself and the lawyer is glowing. They’re very polite to him. The judge even gets up to help him to his seat. Julien is weary to death, but happy.

“Monsieur Courtois,” he says—get that, he said “Monsieur!”—“Monsieur Courtois, new evidence has been presented and …”

He is embarrassed. The lawyer comes to his aid.

“You’re going free, provisionally …”

Julien closes his eyes so they won’t read the agony of relief in his look.

“Obviously,” says the judge, “this evidence calls for further investigation, and we’ll have to ask you to remain at our disposal a few days more …”

He coughs. Julien doesn’t listen to him any more. What does he care what they’ve found out, as long as they let him out.

Frantic

Frantic